(Dear readers, thank you for all your lovely words on this piece. Here are some bits you shared with me on the same day of posting this essay, I appreciate all of you! ❤️)

Fatherlessness and losing a father are two very different concepts. To have a father, to know his love, wisdom, protection, provision, leadership, support, and friendship is priceless and can be replaced by none other. This is not an essay on fatherlessness, this is my mere attempt at faintly capturing a tragic stage that shapes a man —losing his old man.

Some of the most kind, gentle, and wise men I know, have lost their fathers comparatively early in life. I don’t know why fate does this, but is seemingly some sort of rite of passage for the wise man. Accounts of St. Joseph, the father of Christ randomly disappear after the Messiah has all grown up too.

There is a lasting effect to losing one’s father — and I have found Dr. Jordan Peterson to live up to the hype of being the patron saint of men who need a father figure. As you would know, JP has often spoken about the archetypal significance of the father figure and the role of fathers in providing guidance, structure, and support to their children. The loss of a father can be a deeply traumatic experience and affects individuals on both psychological and existential levels. But failing to reconcile with this loss, spells eternal damnation for a young man. This is why it is a rite of passage, the day a man grows into the man.

"I believe that what we become depends on what our fathers teach us at odd moments when they aren’t trying to teach us." - Umberto Eco

To have order in life

According to Carl Jung, who formulated the archetypes — universal symbols or patterns that exist in the collective unconscious and are inherited from our ancestors — the father archetype represents the authority figure, protector, and provider within the psyche who plays a crucial role in shaping our perceptions of power, authority, and identity. Any blow to the father figure shapes our perception of power, and in the best case, enrages a man to take back the lost power in his life. May it be under-compensation at work, a compromised, unfulfilling relationship, or simply vices, the absence of the father, felt as sorely as salt will creep in to make its presence felt in potentiality, authority, and recognition. Jung argued that the father archetype is a fundamental aspect of the human psyche, stemming from our evolutionary past and cultural heritage. It embodies qualities such as wisdom, strength, discipline, and guidance, and it serves as a template for how we also relate to authority figures in our lives, including actual fathers, as well as other authority figures such as teachers, leaders, bosses, and mentors. A man unhealed from the loss of his father will subconsciously face blockages in these relations.

The father archetype is also the pillar of order, stability, and tradition, providing a sense of security and structure in the face of life's uncertainties. We are disciplined as long as we have a strict father watching over us, to crack out of a childish shell, to have consistency, discipline, and integrity when our father is not around, that is when we truly mature. It is one of Jung’s theories that we project the father archetype onto external figures and sometimes even institutions maybe as an attempt to seek guidance and validation from sources of authority that embody these archetypal qualities. The quest for the father continues on… relating to the other pattern

Of heroes, victories, and merit.

We talk about only one aspect of the Oedipal complex, but it extends onto the establishment of the superego, where the father becomes a central figure in a person’s psychosexual and moral development, shaping their conscience and guiding their behavior in accordance with societal expectations. The superego, one of the three components of the human psyche according to Freudian psychology, represents the internalization of societal and parental values, functioning as the moral conscience that guides our behavior and decision-making.

We may hate it but Freud theorized the phallic stage of psychosexual development, typically between the ages of three and six years old which is when a boy harbors hostile feelings toward the same-sex parent (here, the father). He rebels against this figure, often also synonymous with societal expectations and norms, or plain authority, because of his nature. But he comes to be, when he reconciles with the loss of this figure.

In his seminal work, Totem and Taboo (1913), Sigmund Freud explored the origins of morality and societal norms through a psychological lens proposing the concept of the "primal horde,” a primitive human social structure. He draws up an argument that in early human history, the father figure held absolute power within the tribe, with exclusive rights to sexual access to the females. It was because of this that the sons within the tribe would harbor this unconscious desire to overthrow the father to possess the females for themselves which led to conflict and the eventual establishment of societal norms and taboos against such wants. This is somewhat related to the social conditioning of males that I talk about in my essay on the cultural castration of men, linked here. It is where the fight starts.

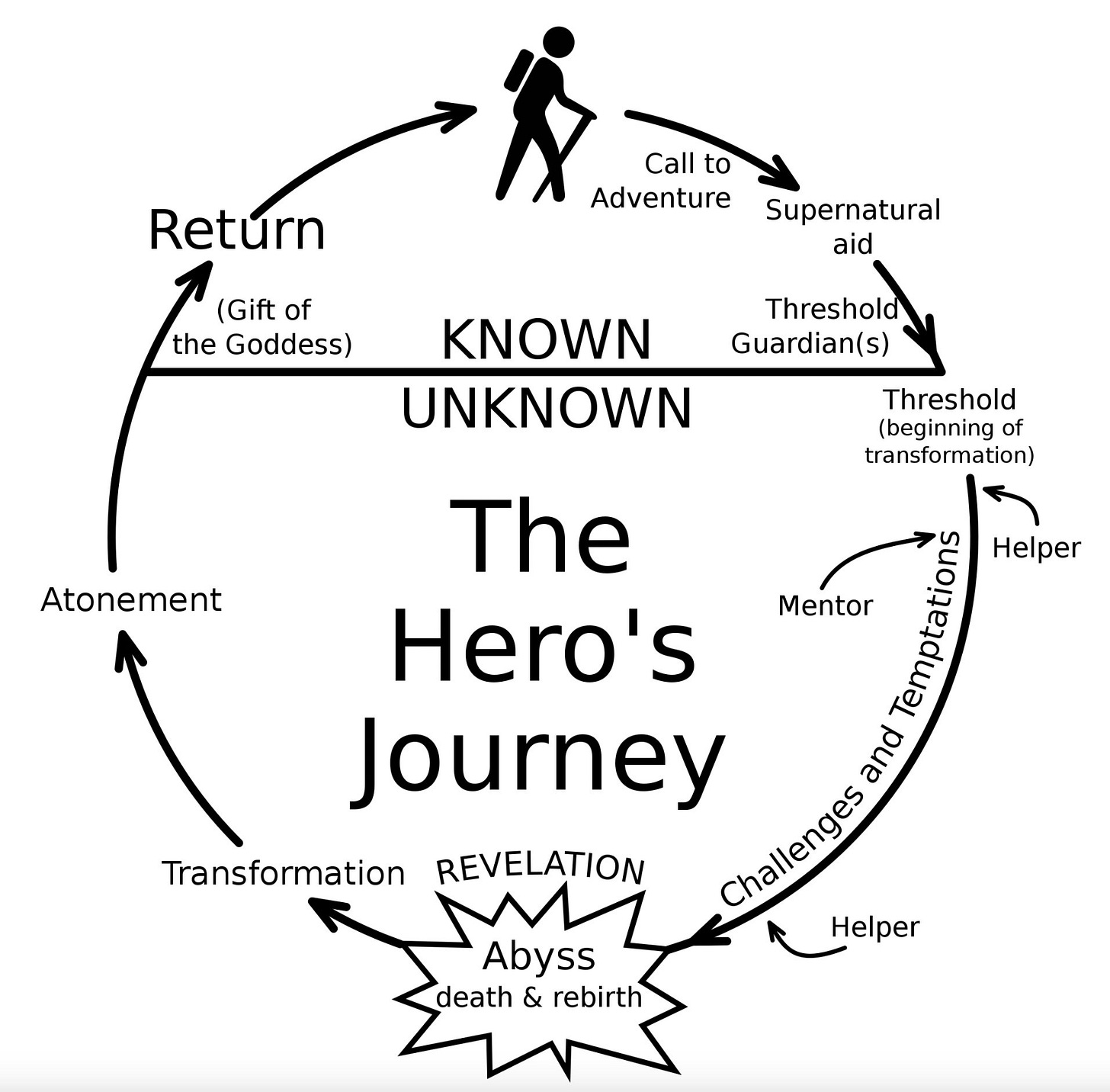

If you find JBP to be the Wallmart version of the renowned scholar of mythology and comparative religion, Joseph Campbell, let’s turn to he who extensively explored the father archetype and its significance in mythology and folklore. In his literature of The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell outlines the monomyth, or hero's journey, a recurring narrative pattern found in myths and stories from diverse cultures worldwide. Central to this archetype is the figure of the father, often portrayed as a wise mentor, guardian, or antagonist who sets the hero on their transformative journey of self-discovery and growth. Campbell also elucidates the symbolism of the father archetype when he writes, "A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man." It is this encounter with the father figure that serves as a pivotal moment in the hero's journey, a transition from the ordinary world to the realm of adventure and transformation. To connect this a little more to the theme I am aiming for, Campbell explores the father archetype quite well in the context of initiation rituals and rites of passage found in traditional societies. These rituals often involve a symbolic death and rebirth, mirroring the hero's journey of self-discovery and spiritual awakening.

“Only birth can conquer death—the birth, not of the old thing again, but of something new.” - Joseph Campbell, Hero With a Thousand Faces

And that is why a man has to grow through this phase to become the new thing - a new man.

To move forward with Apatheia,

The idea of the father figure is frequently connected to virtue and moral guidance in Stoic philosophy. The Stoics placed extreme emphasis on the virtues of wisdom, courage (read more in my essay on how to have courage), justice, and temperance as well as living in harmony with the natural world. In both the literal and familial sense, the father figure leads people toward moral authority and virtue by serving as an example of morality and self-improvement. Ancient Greek and Roman literature and mythology are replete with stories and legends featuring father figures who embody various virtues and qualities. For example, in Homer's Odyssey one of the most important stories ever told, revolves around the protagonist Odysseus embarking on a journey to return home to his son Telemachus, symbolizing the importance of familial bonds and paternal guidance.

One of the central tenets of Stoicism is the notion of apatheia, or emotional equanimity, which involves cultivating inner strength and resilience in the face of adversity. Death is something that requires us to let go of obsessing over what is beyond our control and focus on what can be controlled—namely, our thoughts, actions, and attitudes, all aspects that need a radical shift in the life of a man beyond this tragedy.

When one beautiful thing ends, another beautiful one must begin, it is only right and just.

Turning to the other half

The one reward for overcoming the grief of losing a father, or much rather — triumphing over it, ie., to make your father proud of your courage, acts, and discipline, is the potential for growth, resilience, and mostly, deepened relationships. It is a commonly acknowledged axiom that men are systems and things-oriented while women are people and relationship-oriented. But as a man navigates this emotional terrain, he is not just inspired and by some divine force compelled to conquer and succeed, but also finds his heart tugged at for the need of solace, strength, and support. What better place to find this, other than in his wife, who becomes a pillar of stability and comfort during his time of need?

Aging Well - Why Love is Necessary in A Marriage

I’ve had conversations with numerous people; single, engaged, married, divorced, about marriage, and their understanding of the recipe to build a good one. Some argue, like some new age therapists, that love is not all that necessary in marriage. Their argument is,

In literature and mythology, there are numerous examples of characters who face the loss of a father figure and subsequently turn to their spouses for support and guidance. Some of my favourites lie in the recently read epic of Gilgamesh, where the titular hero mourns the death of his friend Enkidu and seeks solace from his wife, who provides him with emotional support and wise counsel, and Hamlet by Shakespeare where he grapples with the grief of losing his father and finds solace in his relationship with Ophelia. Although their relationship is complex and ultimately tragic, Ophelia serves as a source of comfort and understanding for Hamlet during his time of mourning.

When a man comes to himself

I call this a rite of passage because it is when a man comes to light with his responsibilities.

“And so men grow by having responsibility laid upon them, the burden of other people’s business. Their powers are put out at interest, and they get usury in kind. They are like men multiplied. Each counts manifold.” - Woodrow Wilson

As the great Woodrow Wilson proposes — men grow by having responsibilities laid out for them — so the absence of the primary responsibility-bearer is a new cross to carry for the heir. This would explain why men love power, greatness, feeling needed and successful, because it allows them to grow, to conquer, to build. It offers pleasures and rejuvenation, like a chilled beer after a redundant household chore carried out well and crossed from the wife’s to-do.

When a man comes to himself and becomes his own man, he sees beyond the binary of everyday life, he rids himself of previously, loosely held notions, and fixes his mind on virtue and principles again, he looks at chaos, and can part it like the Red Sea, because of this newfound wisdom.

“He had come to himself—to the full realization of his powers, the true and clear perception of what it was his mind demanded for its satisfaction. His faculties were consciously stretched to their right measure, were at last exercised at their best. He felt the keen zest, not of success merely, but also of honor, and was raised to a sort of majesty among his fellow-men, who attended him in death like a dead sovereign. He had died dwarfed had he not broken the bonds of mere money-getting; would never have known himself had he not learned how to spend it; and ambition itself could not have shown him a straighter road to fame. This is the positive side of a man’s discovery of the way in which his faculties are to be made to fit into the world’s affairs, and released for effort in a way that will bring real satisfaction.”

Perhaps fate throws the tragic ball a good man’s way to bring him ‘to the Light.’ As I end with another quote from the revered President Wilson:

“It brings him into a light which guides instead of deceiving him; a light which does not make the way look cold to any man whose eyes are fit for use in the open, but which shines wholesomely, rather upon the obvious path, like the honest rays of the frank sun, and makes traveling both safe and cheerful.”

Thank you for reading!

If you enjoyed this, write back to me (as most of you do, and I trulyyyy appreciate!) or leave a comment. If you aren’t a subscriber, do join in, I would love to have you on the list!

My other essay on grief:

Great Expectations and a Tale of Two Quotes

(While this may not be the most stunning piece of literature I have written, not a day goes by since I wrote this essay, that I don't think about it.) I was talking to this honey-eyed boy with leukemia, whose mother had pushed him into therapy, although I'm pretty sure he didn't need it. He didn't have very long to live, but whatever he told me that day,…

Here’s another essay you may like :)

Stop Existing, Start Living

Your life begins the moment you decide it does — and not someone else. To live, you must live life on your own terms - what you choose, what makes you happy, healthy, and lets you thrive. To direct your life in the direction of things you don’t want is to never really choose what you